A recent order passed by a Sessions Court in Goa has reignited an important debate in criminal procedural jurisprudence: Does a court have the power to grant interim protection while considering an application for anticipatory bail under Section 482 of the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS)?

In the matter under discussion, the learned Sessions Court declined to grant interim relief on the ground that Section 482 of BNSS does not expressly provide for interim protection, unlike Section 438 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC). The Court proceeded on the premise that the absence of an explicit statutory clause prevented it from granting ad-interim anticipatory relief. It is sometimes argued during submissions that interim relief cannot be granted because Section 482 does not specifically contain such a provision. This line of reasoning might have been acceptable only in a situation where no judicial precedent existed. However, when binding judicial precedent is available, the Court is required to follow that precedent.

This approach stands in direct contradiction to the binding precedent of the Bombay High Court, Goa Bench, specifically in Criminal Writ Petition No. 618 of 2024 (F) read with Criminal Writ Petition No. 619 of 2024 (F). In this authoritative decision, the High Court clearly held that the power to grant interim protection is inherent in the jurisdiction to hear and decide an anticipatory bail application, even under Section 482 of BNSS. The Court reasoned that the principles underlying Section 482 of BNSS are pari materia with those under Section 438 of CrPC, and the absence of an explicit clause cannot dilute the Court’s ability to safeguard liberty while the application is pending.

The refusal to grant interim protection contrary to binding precedent raises significant legal concerns. Judicial training inputs or interpretative impressions cannot override the law declared by the High Court. Under the constitutional scheme, High Court judgments are binding on all subordinate courts, and non-observance of such binding authority results in a legally unsustainable order.

It is important to reiterate that the High Court has recognised that the grant of interim relief—though discretionary and dependent on the facts of each case—is nonetheless a part of the Court’s judicial duty when circumstances justify such protection. This discretion cannot be negated by treating the power as non-existent.

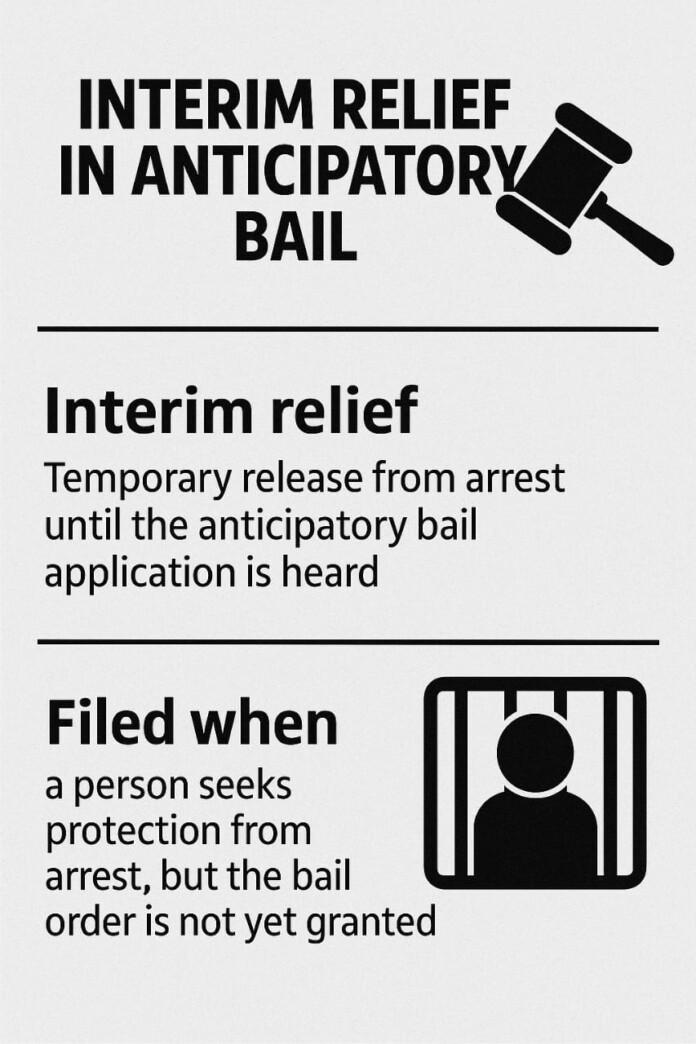

The consequences of denying interim relief can be severe. Without such protection, an applicant may face arrest even before the anticipatory bail application is heard—an outcome that defeats the very purpose of the remedy. The High Court has emphasised that interim protection is not a procedural luxury but a constitutional safeguard essential for preserving personal liberty.

In the transitional BNSS era, where interpretative challenges are expected, it becomes even more important that courts rely on binding judicial precedent. Interim relief in anticipatory bail matters is not governed by legislative silence but by judicial responsibility—exercised cautiously and in accordance with established precedent. Until the Supreme Court holds otherwise, the ratio laid down in Criminal Writ Petition No. 618 of 2024 (F) read with Criminal Writ Petition No. 619 of 2024 (F) remains binding law in Goa.

This article is written by Adv. Vinayak D. Porob with the assistance of Adv. Prathamesh Korgaonkar and Adv. Eshwar Khobrekar. The observations in this article are made purely in the nature of legal analysis and academic discussion. The intention is not to scandalise, criticise, or lower the authority of any court or judicial officer, nor to commit contempt of court in any manner. The sole objective is to highlight the legal position as settled by the binding precedent.